THE LIFE OF ST. THERESE OF LISIEUX

"...I will spend my Heaven doing good on earth..."

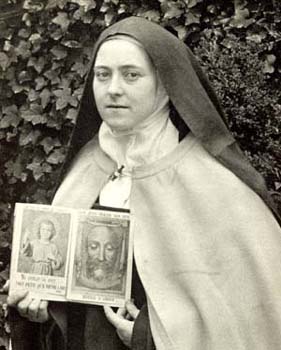

Saint Thérèse of Lisieux, born Marie-Françoise-Thérèse Martin, in Alencon, France, on January 2, 1873, and baptized shortly after at the Basilica of Notre-Dame d'Alencon, was a French Carmelite nun who died at the age of 24 on September 30, 1897. Her religious name was Sr. Thérèse of the Child Jesus and the Holy Face, but after her death she became known as "The Little Flower of Jesus" or simply “The Little Flower”.

Thérèse was the ninth and last child of Azelie (Zelie) Guerin, a lacemaker, and Louis Martin, a jeweler and watchmaker. Both her parents were devout Catholics. Louis had tried to become a monk, wanting to

Thérèse was the ninth and last child of Azelie (Zelie) Guerin, a lacemaker, and Louis Martin, a jeweler and watchmaker. Both her parents were devout Catholics. Louis had tried to become a monk, wanting to enter the Augustinian Monastery of the Great St. Bernard, but had been refused because he knew no Latin and couldn't seem to learn it. Zélie, possessed of a strong, active temperament, wished to serve the sick, and had also considered becoming a religious, but the superior of the sisters of the Hotel-Dieu had discouraged her inquiry outright. Disappointed, Zélie learned the trade of lacemaking. She excelled in it and set up her own business on Rue Saint-Blaise at age 22. (For information and pictures of St. Thérèse's four sisters, please see the link, "The Martin Sisters".)

enter the Augustinian Monastery of the Great St. Bernard, but had been refused because he knew no Latin and couldn't seem to learn it. Zélie, possessed of a strong, active temperament, wished to serve the sick, and had also considered becoming a religious, but the superior of the sisters of the Hotel-Dieu had discouraged her inquiry outright. Disappointed, Zélie learned the trade of lacemaking. She excelled in it and set up her own business on Rue Saint-Blaise at age 22. (For information and pictures of St. Thérèse's four sisters, please see the link, "The Martin Sisters".)

Thérèse felt an early call to religious life and, in 1888 at the age of 15, overcame various obstacles to become a nun, joining two of her older sisters in the cloistered Carmelite community of Lisieux, Normandy. After nine years as a Carmelite religious, having fulfilled various offices such as sacristan and assistant to the novice mistress, and having spent the last eighteen months in Carmel in a dark night of faith, she died of Tuberculosis at the age of 24. The impact of The Story of A Soul, a collection of her autobiographical manuscripts, printed and distributed a year after her death to an initially very limited audience, was great; and she rapidly became one of the most popular saints of the twentieth century. Pope Piux XI made her the "star of his pontificate". She was beatified in 1923, and canonized in 1925. Thérèse was declared co-patron of the missions with Francis Xavier in 1927, and named co-patron of France with Joan of Arc in 1944. On October 19, 1997, Pope John Paul II declared her the thirty-third Doctor of the Church, the youngest person, and only the third woman, to be so honored. Devotion to Thérèse has developed around the world.

Thérèse lived a hidden life and "wanted to be unknown," yet became popular after her death through her spiritual autobiography. She also left letters, poems, religious plays, and prayers—even her last conversations were recorded by her sisters. Photographs and paintings—mostly the work of her sister Céline—further led to her being recognized by millions of men and women.

The depth of her spirituality, of which she said, "my way is all confidence and love," has inspired many believers. In the face of her littleness and nothingness, she trusted in God to be her sanctity. She wanted to go to Heaven by an entirely new little way. "I wanted to find an elevator that would raise me to Jesus." The elevator, she wrote, would be “the arms of Jesus lifting me in all my littleness.”

DETAILS OF HER CHILDHOOD AND HER VOCATION

Soon after her birth, the outlook for the survival of Thérèse Martin was very grim. Enteritis, which had already claimed the lives of at least three of the four of her siblings who died young, threatened Thérèse, and she had to be entrusted to a wet nurse, Rose Taillé, who had already nursed two of the Martin children. Rose had her own children and could not live with the Martins, so Thérèse was sent to live with her in the forests of the Bodage at Semalle. On Holy Thursday, April 2, 1874, when she was 15 months old, she was returned to Alençon where her family surrounded her with affection. She was educated in a very Catholic environment, including Mass attendance at 5:30 a.m., the strict observance of fasts, and prayer to the rhythm of the liturgical year. The Martins also practiced charity, visiting the sick and elderly and welcoming the occasional vagabond to their table.

Therese like to play at being a nun. One day she went as far as to wish her mother would die; when scolded, she explained that she wanted the happiness of Paradise for her dear mother. Described as generally a happy child, the mother's humorous letters from this time provide a vivid picture of the baby Thérèse. In a letter to Pauline when Thérèse was three: "She is intelligent enough, but not nearly so docile as her sister Céline. When she says NO, nothing can make her change, and she can be terribly obstinate. You could keep her down in the cellar all day without getting a yes out of her; she would rather sleep there." Mischievous and impish, she gave joy to her family but she was emotional, too, and often cried. "I hear the baby calling me Mama! as she goes down the stairs. On every step, she calls out Mama! and if I don't respond every time, she remains there without going either forward or back." (Zelie Martin to Pauline in November 1875)

In 1865, Zelie began complaining of breast pain and she was found to have a tumor; in December 1876 a doctor told her of the seriousness of the tumor. Feeling the approach of death, Zelie wrote to Pauline in the Spring of 1877, "You and Marie will have no difficulties withThérèse's upbringing. Her disposition is so good. She is a chosen spirit." On August 28, 1877, Zélie Martin died of breast cancer at age 45, when Thérèse was barely 4 1/2 years old. Her mother's death dealt Thérèse a severe blow and later she would consider that the first part of her life stopped that day. She wrote: "Every detail of my mother's illness is still with me, especially her last weeks on earth." Three months after Zélie died, Louis Martin left Alençon, where he had spent his youth and marriage, and moved to Lisieux in the Calvados Department of Normandy, where Zelie's pharmacist brother, Isidore Guérin,

lived with his wife and two daughters. In her last months, Zélie had given up the lace business; after her death, Louis sold it. Louis leased a pretty, spacious country house, Les Buissonnets, situated in a large garden on the slope of a hill overlooking the town. Looking back, Thérèse would see the move to Les Buissonnets as the beginning of the "second period of my life, the most painful of the three: it extends from the age of four-and-a-half to fourteen, the time when I rediscovered my childhood character, and entered into the serious side of life." In Lisieux, Pauline took on the role of Thérèse's Mama. She took this role seriously, and Thérèse grew especially close to her and to Céline, the sister closest to her in youth. Thérèse discovered the community life of school something for which she was unprepared. She wrote later that the five years of school were the saddest of her life and she found consolation only in the presence at the school of her dear Céline.

lived with his wife and two daughters. In her last months, Zélie had given up the lace business; after her death, Louis sold it. Louis leased a pretty, spacious country house, Les Buissonnets, situated in a large garden on the slope of a hill overlooking the town. Looking back, Thérèse would see the move to Les Buissonnets as the beginning of the "second period of my life, the most painful of the three: it extends from the age of four-and-a-half to fourteen, the time when I rediscovered my childhood character, and entered into the serious side of life." In Lisieux, Pauline took on the role of Thérèse's Mama. She took this role seriously, and Thérèse grew especially close to her and to Céline, the sister closest to her in youth. Thérèse discovered the community life of school something for which she was unprepared. She wrote later that the five years of school were the saddest of her life and she found consolation only in the presence at the school of her dear Céline.

Thér èse was taught at home until she was eight and a half, and then entered the school kept by the Benedictine nuns of the Abbey of Notre Dame du Pre in Lisieux. Thérèse, taught well and carefully by Marie and Pauline, found herself at the top of the class, except for writing and arithmetic. However, because of her young age and high grades, she was bullied. The one who bullied her the most was a girl of fourteen who did poorly at school. Thérèse suffered very much as a result of her sensitivity, and she cried in silence. Furthermore, the boisterous games at recreation were not to her taste. She preferred to tell stories or look after the little ones in the infants' class. "The five years I spent at school were the saddest of my life, and if my dear Céline had not been with me I could not have stayed there for a single month without falling ill." On her free days she became more and more attached to Marie Guérin, the younger of her two cousins in Lisieux. The two girls would play at being anchorites, as the great Teresa had once played with her brother. And every evening she plunged into the family circle. "Fortunately, I could go home every evening and then I cheered up. I used to jump on Father's knee and tell him what marks I had had, and when he kissed me all my troubles were forgotten...I needed this sort of encouragement so much." Yet the tension of the double life and the daily self-conquest placed a strain on Thérèse. Going to school became more and more difficult.

èse was taught at home until she was eight and a half, and then entered the school kept by the Benedictine nuns of the Abbey of Notre Dame du Pre in Lisieux. Thérèse, taught well and carefully by Marie and Pauline, found herself at the top of the class, except for writing and arithmetic. However, because of her young age and high grades, she was bullied. The one who bullied her the most was a girl of fourteen who did poorly at school. Thérèse suffered very much as a result of her sensitivity, and she cried in silence. Furthermore, the boisterous games at recreation were not to her taste. She preferred to tell stories or look after the little ones in the infants' class. "The five years I spent at school were the saddest of my life, and if my dear Céline had not been with me I could not have stayed there for a single month without falling ill." On her free days she became more and more attached to Marie Guérin, the younger of her two cousins in Lisieux. The two girls would play at being anchorites, as the great Teresa had once played with her brother. And every evening she plunged into the family circle. "Fortunately, I could go home every evening and then I cheered up. I used to jump on Father's knee and tell him what marks I had had, and when he kissed me all my troubles were forgotten...I needed this sort of encouragement so much." Yet the tension of the double life and the daily self-conquest placed a strain on Thérèse. Going to school became more and more difficult.

In October 1862, when she was nine years old, her sister Pauline who had acted as a "second mother" to her, entered the Carmelite monastery at Lisieux. Thérèse was devastated. She understood that Pauline was cloistered and that she would never come back. "I said in the depths of my heart: Pauline is lost to me!" The shock reawakened in her the trauma caused by her mother's death. She also wanted to join the Carmelites, but was told she was too young. Yet Thérèse so impressed Mother Marie Gonzague, prioress at the time of Pauline's entry into the community, that she wrote to comfort her, calling Thérèse "my future little daughter."

At this time, Thérèse was often sick; she began to suffer from nervous tremors. The tremors started one night after her uncle took her for a walk and began to talk about Zélie. Assuming that she was cold, the family covered Thérèse with blankets, but the tremors continued; she clenched her teeth and could not speak. The family called Dr. Notta, who could make no diagnosis. In 1882, Dr Gayral diagnosed that Thérèse "reacts to an emotional frustration with a neurotic attack." An alarmed, but cloistered, Pauline began to write letters to Thérèse and attempted various strategies to intervene. Eventually, Thérèse recovered after she had turned to gaze at the statue of the Virgin Mary placed in Marie's room, where Thérèse had been moved. She reported on May 13, 1883, that she had seen the Virgin smile at her. She wrote: "Our Blessed Lady has come to me, she has smiled upon me. How happy I am." However, when Thérèse told the Carmelite nuns about this vision at the request of her eldest sister Marie, God allowed her to find suffering through the remembrance of this favor. “The memory of this great grace caused me real spiritual anguish.”

In October 1886, her oldest sister, Marie, entered the same Carmelite monastery, adding to Thérèse's grief. The warm atmosphere at Les Buissonnets, so necessary to her, was disappearing. Now only she and Céline remained with their father. Her frequent tears made some friends think she had a weak character and the Guérins indeed shared this opinion. Thérèse also suffered from scruples, a condition experienced by other saints such as Alphonsus Liguori, also a Doctor of the Church, and Ignatius Loyola, the founder of the Jesuits. She wrote: "One would have to pass through this martyrdom to understand it well, and for me to express what I experienced for a year and a half would be impossible."

Christmas Eve 1886 was a turning point in the life of Thérèse; she called it her "complete conversion." Years later she stated that on that night she overcame the pressures she had faced since the death of her m other and said that "God worked a little miracle to make me grow up in an instant." "On that blessed night ... Jesus, who saw fit to make Himself a child out of love for me, saw fit to have me come forth from the swaddling clothes and imperfections of childhood."

other and said that "God worked a little miracle to make me grow up in an instant." "On that blessed night ... Jesus, who saw fit to make Himself a child out of love for me, saw fit to have me come forth from the swaddling clothes and imperfections of childhood."

On Christmas Eve 1886, Louis Martin and his daughters, Léonie, Céline and Thérèse, had attended the Midnight Mass at the cathedral in Lisieux. On December 1st of that year, Léonie, covered in eczema and hiding her hair under a short mantilla, had returned to Les Buissonnets after just seven weeks under the regime of the Poor Clares in Alençon, and her sisters were helping her get over her sense of failure and humiliation. Back at Les Buissonnets, Thérèse, as was the custom for French children, had left her shoes on the hearth, empty in anticipation of gifts, not from Father Christmas but from the Child Jesus, who was imagined to travel through the air bearing toys and cakes. While she was going up the stairs she heard her father say to Celine, "Well, fortunately, this will be the last year for this!” Thérèse began to cry and Céline advised her not to go back downstairs immediately. Then, suddenly, Thérèse pulled herself together and wiped her tears. She ran down the stairs, knelt by the fireplace and unwrapped her surprises as jubilantly as ever. In her account, nine years later, in 1895, she wrote: "In an instant Jesus, content with my good will, accomplished the work I had not been able to do in ten years." After nine sad years she had recovered the strength of soul she had lost when her mother died and, she said, she was to retain it forever. She discovered the joy in self-forgetfulness and added, "I felt, in a word, charity enter my heart, the need to forget myself to make others happy. Since that blessed night, I have not been defeated in any battle, but instead I went from victory to victory and began, so to speak, to “run a giant's course” (Psalms 19:5).

In May 1887, Thérèse approached her 63-year old father Louis, who was recovering from a small stroke, while he sat in the garden one Sunday afternoon and told him that she wanted to celebrate the anniversary of "her conversion" by entering Carmel before Christmas. Louis and Thérèse both broke down and cried, but Louis got up, gently picked a little white flower, root intact, and gave it to her, explaining the care with which God brought it into being and preserved it until that day. Thérèse later wrote: "while I listened I believed I was hearing my own story." To Therese, the flower seemed a symbol of herself. Thérèse then renewed her attempts to join the Carmel, but the priest-superior of the monastery would not allow it on account of her youth.

In May 1887, Thérèse approached her 63-year old father Louis, who was recovering from a small stroke, while he sat in the garden one Sunday afternoon and told him that she wanted to celebrate the anniversary of "her conversion" by entering Carmel before Christmas. Louis and Thérèse both broke down and cried, but Louis got up, gently picked a little white flower, root intact, and gave it to her, explaining the care with which God brought it into being and preserved it until that day. Thérèse later wrote: "while I listened I believed I was hearing my own story." To Therese, the flower seemed a symbol of herself. Thérèse then renewed her attempts to join the Carmel, but the priest-superior of the monastery would not allow it on account of her youth.

During the summer, French newspapers were filled with the story of Henri Pranzini, convicted of the brutal murder of two women and a child. To the outraged public, Pranzini represented all that threatened the decent way of life in France. In July and August 1887, Thérèse prayed hard for the conversion of Pranzini, so his soul could be saved, yet Pranzini showed no remorse. At the end of August, the newspapers reported that just as Pranzini's neck was placed on the guillotine, he had grabbed a crucifix and kissed it three times. Thérèse was ecstatic and believed that her prayers had saved him. She continued to pray for Pranzini after his death.

In November 1887, Louis took Céline and Thérèse on a diocesan pilgrimage to Rome for the priestly jubilee of Pope Leo XIII. The youngest in the pilgrimage, bright and pretty, Thérèse did not go unnoticed. In Bologna a student boldly jostled against her on purpose. On November 20, 1887, during a general audience with the Pope, an old man of seventy-seven, Thérèse, in her turn, approached him, kissed his slipper instead of his hand, and said, “Most Holy Father, I have a great favour to ask of you” and then asked his permission to enter the Cloister at age 15. (Later, that evening, she wrote to Pauline, "the Pope is so old that you would think he is dead".) The Pope replied, "Well, my child, do what the superiors decide. You will enter if it is God's Will," and he blessed her. She refused to leave his feet, and the Swiss Guard had to carry her out of the room.

Soon after that, the Bishop of Bayeux authorized the prioress to receive Thérèse, and on April 9, 1888, she became a Carmelite postulant. In 1889, her father suffered a stroke and was taken to a private sanatorium, the Bon Sauveur at Caen, where he remained for three years before returning to Lisieux in 1892. He died on July 29, 1894. Upon his death, Céline, who had been caring for him, entered the same Carmel as her three sisters on September 14, 1894; their cousin, Marie Guérin, entered on August 15, 1895. Léonie, after several attempts, became Sister Françoise-Thérèse, a nun in the Order of the Visitation of Holy Mary at Caen, where she died in 1941.

The monastery Thérèse entered was not an old-established house with a great tradition. In 1838, two nuns fro m the Poitiers Carmel had been sent out to found a house in Lisieux. One of them, Mother Geneviève of St Teresa, was still living when Thérèse entered. In fact, the second wing of the convent, containing the cells and sickrooms in which Therese was to live and die, had been standing only ten years. What Thérèse found when she entered was a

m the Poitiers Carmel had been sent out to found a house in Lisieux. One of them, Mother Geneviève of St Teresa, was still living when Thérèse entered. In fact, the second wing of the convent, containing the cells and sickrooms in which Therese was to live and die, had been standing only ten years. What Thérèse found when she entered was a

community of very aged nuns, some odd and cranky, some sick and troubled, some lukewarm and complacent. Almost all of the sisters came from the petty bourgeois and artisan class. The Prioress and Novice Mistress were of old Norman nobility. Probably the Martin sisters alone represented the new class of the rising bourgeoisie.

The Carmelite order had been reformed in the sixteenth century by Teresa of Avila. The times of silence and of solitude were many, but the foundress had also planned time for work and relaxation in common, believing that the austerity of the life should not hinder sisterly and joyful relations. The Carmel of Lisieux in 1888 had 26 nuns from very different classes and backgrounds. For the majority of the life of Thérèse, the prioress would be Mother Marie de Gonzague, born Marie-Adéle-Rosalie Davy de Virville. When Thérèse entered the convent, Mother Marie was 54, a woman of changeable humor who sometimes used her authority in a capricious manner; this had for effect a certain laxity in the observance of established rules.

Thérèse's time as a postulant began on the Feast of the Annunciation. S he felt peace after she received Communion that day and later wrote, "At last my desires were realized, and I cannot describe the deep sweet peace which filled my soul. This peace has remained with me during the eight and a half years of my life here, and has never left me—even amid the greatest trials." From her childhood, Thérèse had dreamed of the desert to which God would some day lead her. Now she had entered that desert. Though she was now reunited with Marie and Pauline, from the first day she began her struggle to win and keep her distance from her sisters. Right at the start Marie de Gonzague, the prioress, had turned the postulant Thérèse over to her eldest sister Marie, who was to teach her to follow the Divine Office. Later she appointed Thérèse assistant to Pauline in the refectory. And when her cousin Marie Guerin also entered, she employed the two together in the sacristy. Thérèse adhered strictly to the rule which forbade all superfluous talk during work. She saw her sisters together only in the hours of common recreation after meals. At such times she would sit down beside whomever she happened to be near, or beside a nun whom she had observed to be downcast, disregarding the tacit and sometimes expressed sensitivity and even jealousy of her biological sisters. "We must apologize to the others for our being four under one roof," she was in the habit of remarking. "When I am dead, you must be very careful not to lead a family life with one another...I did not come to Carmel to be with my sisters; on the contrary, I saw clearly that their presence would cost me dear, for I was determined not to give way to nature."

he felt peace after she received Communion that day and later wrote, "At last my desires were realized, and I cannot describe the deep sweet peace which filled my soul. This peace has remained with me during the eight and a half years of my life here, and has never left me—even amid the greatest trials." From her childhood, Thérèse had dreamed of the desert to which God would some day lead her. Now she had entered that desert. Though she was now reunited with Marie and Pauline, from the first day she began her struggle to win and keep her distance from her sisters. Right at the start Marie de Gonzague, the prioress, had turned the postulant Thérèse over to her eldest sister Marie, who was to teach her to follow the Divine Office. Later she appointed Thérèse assistant to Pauline in the refectory. And when her cousin Marie Guerin also entered, she employed the two together in the sacristy. Thérèse adhered strictly to the rule which forbade all superfluous talk during work. She saw her sisters together only in the hours of common recreation after meals. At such times she would sit down beside whomever she happened to be near, or beside a nun whom she had observed to be downcast, disregarding the tacit and sometimes expressed sensitivity and even jealousy of her biological sisters. "We must apologize to the others for our being four under one roof," she was in the habit of remarking. "When I am dead, you must be very careful not to lead a family life with one another...I did not come to Carmel to be with my sisters; on the contrary, I saw clearly that their presence would cost me dear, for I was determined not to give way to nature."

Though the novice mistress, Sr. Marie of the Angels, (Jeanne de Charmontel), found Thérèse slow, the young postulant adapted well to her new environment. She wrote, "Illusions, the Good Lord gave me the grace to have none on entering Carmel. I found religious life as I had figured, no sacrifice astonished me." She sought above all to conform to the rules and customs of the Carmelites that she learned each day. Later, when Thérèse had become assistant to the novice mistress, she repeated how important respect for the Rule was: "When any break the rule, this is not a reason to justify ourselves. Each must act as if the perfection of the Order depended on her personal conduct." She also affirmed the essential role of obedience in religious life: "When you stop watching the infallible compass [of obedience], as quickly the mind wanders in arid lands where the water of grace is soon lacking." She chose a spiritual director, a Jesuit, Father Pichon. At their first meeting, she made a general confession going back over all her past sins. She came away from it profoundly relieved. The priest who had himself suffered from scruples, understood her and reassured her. A few months later, he left for Canada, and Thérèse would only be able to ask his advice by letter and his replies were rare. During her time as postulant, Thérèse had to endure some bullying from other sisters because of her lack of aptitude for handicrafts and manual work. Sr. St. Vincent de Paul, the finest embroideress in the community, made her feel awkward and even called her "the big nanny goat." Thérèse was in fact the tallest in her family {approx. 5'3}. During her last visit to Trouville at the end of June 1887, Thérèse was called, with her long blond hair, 'the tall English girl.' Like all religious, she discovered the ups and downs related to differences in temperament, character, problems of sensitivities or infirmities. After nine years she wrote plainly, "the lack of judgment, education, the touchiness of some characters, all these things do not make life very pleasant. I know very well that these moral weaknesses are chronic, that there is no hope of cure." But the greatest suffering came from outside Carmel. On June 23, 1888, Louis Martin disappeared from his home and was found days later, in the post office in Le Havre. The incident marked the onset of her father's steep physical and mental decline.

The end of Thérèse's time as a postulant arrived on January 10, 1889, with her taking of the habit. From that time she wore the rough homespun and brown scapular, white wimple and veil, leather belt with rosary, woolen stockings, rope sandals. In her letters from this period of her novitiate, Thérèse returned over and over to the theme of littleness, referring to herself as a grain of sand, an image she borrowed from Pauline. The remainder of her life would be defined by retreat and subtraction. She absorbed the work of John of the Cross, spiritual reading uncommon at the time, especially for such a young nun. "Oh! what insights I have gained from the works of our holy father, St John of the Cross! When I was seventeen and eighteen, I had no other spiritual nourishment." She felt a kinship with this classic writer of the Carmelite Order (though nothing seems to have drawn her to the writings of Teresa of Avila), and with enthusiasm she read his works. Passages from these writings are woven into everything she herself said and wrote.

The end of Thérèse's time as a postulant arrived on January 10, 1889, with her taking of the habit. From that time she wore the rough homespun and brown scapular, white wimple and veil, leather belt with rosary, woolen stockings, rope sandals. In her letters from this period of her novitiate, Thérèse returned over and over to the theme of littleness, referring to herself as a grain of sand, an image she borrowed from Pauline. The remainder of her life would be defined by retreat and subtraction. She absorbed the work of John of the Cross, spiritual reading uncommon at the time, especially for such a young nun. "Oh! what insights I have gained from the works of our holy father, St John of the Cross! When I was seventeen and eighteen, I had no other spiritual nourishment." She felt a kinship with this classic writer of the Carmelite Order (though nothing seems to have drawn her to the writings of Teresa of Avila), and with enthusiasm she read his works. Passages from these writings are woven into everything she herself said and wrote.

With the new name a Carmelite receives when she enters the Order, th ere is always an epithet, e.g., Teresa of Jesus, Elizabeth of the Trinity, Anne of the Angels. The epithet singles out the Mystery which she is supposed to contemplate with special devotion. Thérèse's names in religion must be taken together to define her religious significance. The first name was promised to her at nine by Mother Marie de Gonzague (…of the Child Jesus), and was given to her at her entry into the convent. In itself, veneration of the childhood of Jesus was a Carmelite heritage of the seventeenth century. It concentrated upon the staggering humiliation of divine majesty in assuming the shape of extreme weakness and helplessness. The French Oratory of Jesus and Pierre de Berulle renewed this old devotional practice. Yet when she received the veil, Thérèse herself asked Mother Marie de Gonzague to confer upon her the second name (…of the Holy Face). During the course of her novitiate, contemplation of the Holy Face had nourished her inner life. The Holy Face is an image representing the disfigured face of Jesus during His Passion. Therese meditated on certain pasages from the prophet Isaiah which prefigured Christ. Six weeks before her death she remarked to Pauline, "The words in Isaiah: 'no stateliness here, no majesty, no beauty, one despised, left out of all human reckoning, how should we take any account of him, a man so despised (Is 53:2-3),’ these words were the basis of my whole worship of the Holy Face. I, too, wanted to be without comeliness and beauty..unknown to all creatures." On the eve of her profession she wrote to Sister Marie, “Tomorrow I shall be the bride of Jesus 'whose face was hidden and whom no man knew'—what a union and what a future!” The meditation also helped her understand the humiliating situation of her father.

ere is always an epithet, e.g., Teresa of Jesus, Elizabeth of the Trinity, Anne of the Angels. The epithet singles out the Mystery which she is supposed to contemplate with special devotion. Thérèse's names in religion must be taken together to define her religious significance. The first name was promised to her at nine by Mother Marie de Gonzague (…of the Child Jesus), and was given to her at her entry into the convent. In itself, veneration of the childhood of Jesus was a Carmelite heritage of the seventeenth century. It concentrated upon the staggering humiliation of divine majesty in assuming the shape of extreme weakness and helplessness. The French Oratory of Jesus and Pierre de Berulle renewed this old devotional practice. Yet when she received the veil, Thérèse herself asked Mother Marie de Gonzague to confer upon her the second name (…of the Holy Face). During the course of her novitiate, contemplation of the Holy Face had nourished her inner life. The Holy Face is an image representing the disfigured face of Jesus during His Passion. Therese meditated on certain pasages from the prophet Isaiah which prefigured Christ. Six weeks before her death she remarked to Pauline, "The words in Isaiah: 'no stateliness here, no majesty, no beauty, one despised, left out of all human reckoning, how should we take any account of him, a man so despised (Is 53:2-3),’ these words were the basis of my whole worship of the Holy Face. I, too, wanted to be without comeliness and beauty..unknown to all creatures." On the eve of her profession she wrote to Sister Marie, “Tomorrow I shall be the bride of Jesus 'whose face was hidden and whom no man knew'—what a union and what a future!” The meditation also helped her understand the humiliating situation of her father.

On September 24, the public ceremony followed, filled with “sadness and bitterness”. Thérèse found herself young enough, alone enough, to weep over the absence of Bishop Hugonin and her own father, still confined in the asylum." But Mother Marie de Gonzague wrote to the prioress of Tours: "The angelic child is seventeen and a half, with the sense of a 30 year old, the religious perfection of an old and accomplished novice, and possession of herself; she is a perfect nun.”

The years which followed were those of a maturation of her vocation. Thérèse prayed without great sensitive emotions, she multiplied the small acts of charity and care for others, doing small services, without making a show of them. She accepted criticism in silence, even unjust criticisms, and smiled at the sisters who were unpleasant to her. She prayed always much for priests, and in particular for Father Hyacinthe Loyson, a famous preacher who had been a Sulpician and a Dominican novice before becoming a Carmelite and provincial of his order, but who had left the Catholic Church in 1869. Three years later he married a young widow, a Protestant, with whom he had a son. After major excommunication had been pronounced against him, he continued to travel round France giving lectures. While clerical papers called Loyson a renegade monk, Thérèse prayed for her brother. She offered her last communion on August 19, 1897, for Father Hyacinthe.

On February 20, 1893, Pauline was elected prioress of Carmel and became Mother Agnes. Pauline appointed the former prioress novice mistress and made Thérèse her assistant. The work of guiding the novices would fall primarily to Thérèse. Over the next few years she revealed a talent for clarifying doctrine to those who had not received as much education as she. A kaleidoscope, whose three mirrors transform scraps of coloured paper into beautiful designs, provided an inspired illustration for the Holy Trinitiy. "As long as our actions, even the smallest, do not fall away from the focus of Divine Love, the Holy Trinity, symbolized by the three mirrors, allows them to reflect wonderful beauty. Jesus, who regards us through the little lens, that is to say, through Himself, always sees beauty in everything we do. But if we left the focus of inexpressible love, what would He see? Bits of straw..dirty, worthless actions." Another cherished image was that of the newly invented elevator, a vehicle Thérèse used many times over to describe God's grace, a force that lifts us to heights we can't reach on our own. Her sister Céline's memoir is filled with numerous examples of the teacher Thérèse: Céline: "Oh! When I think how much I have to acquire!" Thérèse: "Rather, how much you have to lose! Jesus Himself will fill your soul with treasures in the same measure that you move your imperfections out of the way.." And Céline recalled a story Thérèse told about egotism. The 28-month-old Thérèse visited Le Mans and was given a basket filled with candies, at the top of which were two sugar rings. “Oh! How wonderful! There is a sugar ring for Céline, too!” On her way to the station, however, the basket overturned, and one of the sugar rings disappeared. “Ah, I no longer have any sugar ring for poor Céline!” Reminding Celine of the incident, Thérèse observed, “See how deeply rooted in us is this self-love! Why was it your (Céline's) sugar ring, and not mine, that was lost?” Martha of Jesus, a novice who spent her childhood in a series of orphanages and who was described by all as emotionally unbalanced with a violent temper, gave witness during the beatification process of the “unusual dedication and presence of her young teacher”: "Thérèse deliberately sought out the company of those nuns whose temperaments she found hardest to bear." What merit was there in acting charitably toward people whom one loved naturally? Thérèse went out of her way to spend time with, and therefore to love, the people she found repellent. It was an effective means of achieving interior poverty, a way to remove a place to rest her head.

The year 1894 brought a national celebration of Joan of Arc. On January 27, 1894, Leo XIII authorized the introduction of her cause of beatification, declaring Joan, the shepherdess from Lorraine “venerable”. Thérèse used Henri Wallon's history of Joan of Arc to help her write two plays. Thérèse wrote two plays in honor of her childhood heroine, the first about Joan's response to the heavenly voices calling her to battle, the second about her resulting martyrdom. The first, called "The Mission of Joan of Arc," was performed at the Carmel on January 21, 1894; and the second, called "Joan of Arc Accomplishes her Mission," was performed on January 21, 1895. In the estimation of one of Thérèse's biographers, Ida Görres, the plays "are scarcely veiled self-portraits." As a side note, at the end of the second play that Thérèse had written on Joan of Arc, the costume she wore almost caught fire. The alcohol stoves used to represent the stake at Rouen set fire to the screen behind which Thérèse stood. Thérèse did not flinch but the incident marked her. The theme of fire would assume an increasingly great place in her writings.

The year 1894 brought a national celebration of Joan of Arc. On January 27, 1894, Leo XIII authorized the introduction of her cause of beatification, declaring Joan, the shepherdess from Lorraine “venerable”. Thérèse used Henri Wallon's history of Joan of Arc to help her write two plays. Thérèse wrote two plays in honor of her childhood heroine, the first about Joan's response to the heavenly voices calling her to battle, the second about her resulting martyrdom. The first, called "The Mission of Joan of Arc," was performed at the Carmel on January 21, 1894; and the second, called "Joan of Arc Accomplishes her Mission," was performed on January 21, 1895. In the estimation of one of Thérèse's biographers, Ida Görres, the plays "are scarcely veiled self-portraits." As a side note, at the end of the second play that Thérèse had written on Joan of Arc, the costume she wore almost caught fire. The alcohol stoves used to represent the stake at Rouen set fire to the screen behind which Thérèse stood. Thérèse did not flinch but the incident marked her. The theme of fire would assume an increasingly great place in her writings.

On July 29, 1894, Louis Martin died. Sick, he had been cared for by Céline. Following his death, and supported by Thérèse's letters and the advice of her other sisters, Celine entered the Lisieux convent on September 14, 1894. With Mother Agnes' permission, she brought her camera and developing materials to Carmel. Céline took many photographs of Thérèse. Even when the images are poorly reproduced, her eyes arrest us. Described as blue or gray, they look darker in photographs. Céline's pictures of her sister contributed to the extraordinary cult of personality that formed in the years after Thérèse's death.

Thérèse entered the Carmel of Lisieux with the determination to become a saint. But, by the end of 1894, six full  calendar years as a Carmelite made her realize how small and insignificant she was. She saw the limitations of all her efforts. She remained small and very far off from the unfailing love that she would wish to practice. She understood then that it was on this very littleness that she must lean to ask God's help. Along with her camera, Céline had brought notebooks with her, passages from the Old Testament, which Thérèse did not have in Carmel. (The Louvain Bible, the translation authorized for French Catholics, did not include an Old Testament). In the notebooks Thérèse found a passage from Proverbs that struck her with particular force. If anyone is a very little one, let him come to me (Proverbs 9:4). And, from the book of Isaiah (66:12-13), she was profoundly struck by another passage: As a mother caresses her child, so I shall console you, I shall carry you at my breast and I shall swing you on my knees." She concluded that Jesus would carry her to the summit of sanctity. The smallness of Thérèse, her limits, became in this way grounds for joy, more than discouragement. It is only in Manuscript C of her autobiography that she gave to this discovery the name of little way (petite voie). Echoes of this way, however, are heard throughout her work. From February 1895, she would regularly sign her letters by adding the words, “very little,” (toute petite) in front of her name.

calendar years as a Carmelite made her realize how small and insignificant she was. She saw the limitations of all her efforts. She remained small and very far off from the unfailing love that she would wish to practice. She understood then that it was on this very littleness that she must lean to ask God's help. Along with her camera, Céline had brought notebooks with her, passages from the Old Testament, which Thérèse did not have in Carmel. (The Louvain Bible, the translation authorized for French Catholics, did not include an Old Testament). In the notebooks Thérèse found a passage from Proverbs that struck her with particular force. If anyone is a very little one, let him come to me (Proverbs 9:4). And, from the book of Isaiah (66:12-13), she was profoundly struck by another passage: As a mother caresses her child, so I shall console you, I shall carry you at my breast and I shall swing you on my knees." She concluded that Jesus would carry her to the summit of sanctity. The smallness of Thérèse, her limits, became in this way grounds for joy, more than discouragement. It is only in Manuscript C of her autobiography that she gave to this discovery the name of little way (petite voie). Echoes of this way, however, are heard throughout her work. From February 1895, she would regularly sign her letters by adding the words, “very little,” (toute petite) in front of her name.

On June 9, 1895, during a Mass celebrating the feast of the Holy Trinity, Thérèse had a sudden inspiration that she must offer herself as a sacrificial victim to merciful love. In her cell she drew up an “Act of Oblation” for herself and for Céline, and on June 11, the two of them knelt before the miraculous Virgin and Thérèse read the document she had written and signed. “In the evening of this life, I shall appear before You with empty hands, for I do not ask you, Lord, to count my works.” According to biographer Ida Gorres, the document echoed the happiness she had felt when Father Alexis Prou, the Franciscan preacher, had assured her that her faults did not cause God sorrow. In the Oblation she wrote : "If through weakness I should chance to fall, may a glance from Your Eyes straightway cleanse my soul, and consume all my imperfections--as fire transforms all things into itself."

Thérèse's final years were marked by a steady decline that she bore resolutely and without complaint. Tuberculosis was the key element of Thérèse's final suffering, but she saw that as part of her spiritual journey. After observing a rigorous Lenten fast in 1896, she went to bed on the eve of Good Friday and felt a joyous sensation. She wrote: "Oh! how sweet this memory really is!... I had scarcely laid my head upon the pillow when I felt something like a bubbling stream mounting to my lips. I didn't know what it was." The next morning she found blood on her handkerchief and understood her fate. Coughing up of blood meant tuberculosis, and tuberculosis meant death. She wrote: "I thought immediately of the joyful thing that I had to learn, so I went over to the window. I was able to see that I was not mistaken. Ah! my soul was filled with a great consolation; I was interiorly persuaded that Jesus, on the anniversary of His own death, wanted to have me hear His first call!"

Thérèse's final years were marked by a steady decline that she bore resolutely and without complaint. Tuberculosis was the key element of Thérèse's final suffering, but she saw that as part of her spiritual journey. After observing a rigorous Lenten fast in 1896, she went to bed on the eve of Good Friday and felt a joyous sensation. She wrote: "Oh! how sweet this memory really is!... I had scarcely laid my head upon the pillow when I felt something like a bubbling stream mounting to my lips. I didn't know what it was." The next morning she found blood on her handkerchief and understood her fate. Coughing up of blood meant tuberculosis, and tuberculosis meant death. She wrote: "I thought immediately of the joyful thing that I had to learn, so I went over to the window. I was able to see that I was not mistaken. Ah! my soul was filled with a great consolation; I was interiorly persuaded that Jesus, on the anniversary of His own death, wanted to have me hear His first call!"

As a result of Tuberculosis, Thérèse suffered terribly. When she was near death, her physical suffering kept increasing so that even the doctor himself was driven to exclaim, “If you only knew what this young nun was suffering!” During the last hours of Thérèse’s life, she said, "I would never have believed it was possible to suffer so much--never, never!”

In July 1897, she made a final move to the monastery infirmary. On August 19, 1897, Thérèse received her last Communion. She died on September 30, 1897, at the young age of 24. On her death-bed, she is reported to have said: "I have reached the point of not being able to suffer any more, because all suffering is sweet to me." Her last words were, "My God, I love you!"

July 1897, she made a final move to the monastery infirmary. On August 19, 1897, Thérèse received her last Communion. She died on September 30, 1897, at the young age of 24. On her death-bed, she is reported to have said: "I have reached the point of not being able to suffer any more, because all suffering is sweet to me." Her last words were, "My God, I love you!"

Thérèse was buried on October 4, 1897, in the Carmelite plot in the municipal cemetery at Lisieux, where Louis and Zelie had been buried. In March 1923, however, before she was beatified, her body was returned to the Carmel of Lisieux, where it remains.

St. Thérèse is known today because of her spiritual memoir, L'histoire d'une âme (The Story of a Soul), which she wrote upon the orders of two prioresses of her monastery, and because of the many miracles worked at her intercession. She began to write "Story of a Soul" in 1895 as a memoir of her childhood, under instructions from her sister Pauline, known in religion as Mother Agnes of Jesus. Mother Agnes gave the order after being prompted by their eldest sister, Sister Marie of the Sacred Heart. While Thérèse was on retreat in September 1896, she wrote a letter to Sister Marie of the Sacred Heart, which also forms part of what was later published as "Story of a Soul."

Pope Pius X signed the decree for the opening of her process of canonization on June 10, 1914. Pope Benedict XV, in order to hasten the process, dispensed with the usual fifty-year delay required between death and beatification. On August 14, 1921, he promulgated the decree on the heroic virtues of Thérèse and gave an address on Thérèse's way of confidence and love, recommending it to the whole Church.

There may, however, have been a political dimension to the speed of proceedings--partly to act as tonic for a nation exhausted by war, or even a retort from the Vatican against the dominant secularism and anti-clericalism of the French government. According to some biographies of Edith Piaf, in 1922 the singer (at the time, an unknown seven-year-old girl) was cured from blindness after a pilgrimagage to the grave of Thérèse, at the time not yet formally canonized.

Thérèse was beatified on April 19, 1923, and canonized on May 17, 1925, by Pope Pius XI, only 28 years after her death. Her feast day was added to the Roman Catholic calendar of saints in 1927 for celebration on October 3rd. In 1969, 42 years later, Pope Paul VI moved it to October 1st, the day after her “dies natalis” (birthday to heaven).

Thérèse of Lisieux is the patron saint of aviators, florists, illness(es), and missions. She is also considered by Catholics to be the patron saint of Russia, although the Russiain Orthodox Church does not recognize either her canonization or her patronage. In 1927, Pope Pius XI named Thérèse a patroness of the missions and in 1944 Pope Pius XII named her co-patroness of France alongside St. Joan of Arc.

By the Apostolic Letter Divini Amoris Scientia (The Science of Divine Love) of October 19, 1997, Pope John Paul II declared her one of the thirty-three Doctors of the Church, one of only three women so named, the others being Teresa of Avila (Saint Teresa of Jesus) and Catherine of Siena. Thérèse was the only saint to be named a Doctor of the Church during Pope John Paul II's pontificate.

More Quotes by St. Thérèse

In her quest for sanctity, she believed that it was not necessary to accomplish heroic acts, or "great deeds", in order to attain holiness and to express her love of God. She wrote, "Love proves itself by deeds, so how am I to show my love? Great deeds are forbidden me. The only way I can prove my love is by scattering flowers and these flowers are every little sacrifice, every glance and word, and the doing of the least actions for love." This little way of Therese is the foundation of her spirituality. Within the Catholic Church, Thérèse's way was known for some time as "the little way of spiritual childhood," but Thérèse actually wrote "little way" only once, and she never wrote the phrase "spiritual childhood." It was her sister Pauline who, after Thérèse's death, adopted the phrase "the little way of spiritual childhood" to interpret Thérèse's path. Years after Thérèse's death, a Carmelite of Lisieux asked Pauline about this phrase and Pauline answered spontaneously, "But you know well that Thérèse never used it! It is mine." In May 1897, Thérèse wrote to Father Adolphe Roulland, "My way is all confidence and love." To Maurice Bellière she wrote "and I, with my way, will do more than you, so I hope that one day Jesus will make you walk by the same way as me."

"Sometimes, when I read spiritual treatises in which perfection is shown with a thousand obstacles, surrounded by a crowd of illusions, my poor little mind quickly tires. I close the learned book which is breaking my head and drying up my heart, and I take up Holy Scripture. Then all seems luminous to me; a single word uncovers for my soul infinite horizons; perfection seems simple; I see that it is enough to recognize one's nothingness and to abandon oneself, like a child, into God's arms. Leaving to great souls, to great minds, the beautiful books I cannot understand, I rejoice to be little because only children, and those who are like them, will be admitted to the heavenly banquet."

"For me, prayer is a movement of the heart; it is a simple glance toward Heaven; it is a cry of gratitude and love in times of trial as well as in times of joy; finally, it is something great, supernatural, which expands my soul and unites me to Jesus. . . . I have not the courage to look through books for beautiful prayers.... I do like a child who does not know how to read; I say very simply to God what I want to say, and He always understands me."

To view a video of the exhumation of the body of St. Therese, please click here (x)